Özgür Gürbüz-Perspectives/July 2013

For an ecologist, Turkey’s growth

strategy shows some very alarming numbers. Producers looking for markets will

be pleased with an economic mobility fed by consumption and Turkey’s domestic

demand, but those who see the growth in Turkey in a positive light are ignoring

the fact that in Turkey, audits and legal processes go unmanaged, sustainable

development is given lip service but never acted upon, individuals’ ideas and

suggestions fall on deaf ears, and social costs go unheeded. There are fresh

offerings to the god of growth every day: rivers, forests, clean air, and human

beings. Workers are killed at construction sites, rivers are blocked by dams,

shorelines and forests are distorted by construction. Ecologists and supporters

of market-focus growth might not be of the same mind most of the time, but both

groups converge on one crucial point: Are there enough sources of energy to

support Turkey’s economic growth? Or, as posed by an environmentalist:

Will the effects of this growth impact natural assets at an acceptable level or

not? In order to answer this question, it is important first to look at

Turkey’s current energy situation, and then to look at the estimated demands in

growth and energy

Dependence on external energy

sources

Turkey imports over 70% of its

energy.*1 One of the economic targets of the Justice and Development Party

(Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AKP) when they came into power was a major

increase in growth. But the AKP also wants to lessen Turkey’s dependency on

external sources for its domestic energy needs. The AKP’s desired increase in

economic growth has only been partially successful. In 2002 when they came to

power, Turkey depended on foreign sources for 69% of domestic energy needs; by

2010, this rate had increased to 73%. Turkey is dependent on foreign sources

for 98% of its natural gas and 92% of its petrol. New domestic explorations are

underway to make Turkey less dependent on foreign petrol sources, but there

hasn’t been any noteworthy activity to manage domestic demand. On the contrary,

policies supporting the construction of new highways, bridges, and private

vehicle ownership only promote petrol consumption. Turkey is decreasing its use

of natural gas in generating power and promoting the use of imported coal and

nuclear energy over imported natural gas. But the use of natural gas in private

households is widespread, and inadequate insulation in newly constructed

housing only serves to fuel the demand. In 2012, Turkey imported a record high

of 43 billion m³ of natural gas, up from 17 billion m³ in 2002. Even Deloitte’s

modest estimate indicated that by 2017 Turkey will import 50 to 60 billion m³

of natural gas per year.*2

Reducing dependence on imported

resources besides natural gas is essential, especially reducing the state’s

reliance on imported coal. In Turkey, 44% of domestic lignite pits are already

being used to generate power.*3 The Ministry is planning to harness the entire

potential of domestic coal to power the economy by 2023.*4 The ironic fact of

the matter, however, is that according to the Electricity Energy Market and

Supply Security Strategy Paper published in 2009, many natural resources –not just coal– will be entirely

consumed by the year 2023. Nevertheless, the Paper outlines the following

targets:

• Full use of hydroelectric

potential, technically and economically, for generating electricity by 2023.

• Increase of wind power installed

capacity to 20,000 megawatts by 2023.

• Maximized use of Turkey’s

600-megawatt geothermal electricity generation potential.

• All of which will result in the

reduction of the ratio of natural gas used in the total generation of power to

30%. (As of April 2012, natural gas comprised 47.1% of total power

generation.*5)

This strategic paper does not

mention any specific targets for solar energy or energy efficiency - both of

which would have been important in decreasing dependence on imported energy-

and coal, another imported resource, is given the green light. The same

government that plans to counteract its dependency on imported energy by

constructing a hydroelectric plant on every river in the country also approves

of imported coal; this ‘‘strategic’’ paper might not be so strategic after all.

The paper is also unable to answer the pressing question of how Turkey will be

able to shift to fully imported energy after the year 2023 when all of its

domestic resources have been consumed. If over the next decade the increasing

demand for energy does not slow, and if Turkey has indeed consumed all its

domestic resources by utilizing the full potential of its domestic coal and

hydroelectric energy sources by 2023 as planned, then it seems likely that

Turkey is headed for an energy gap. As it is, the government is adamant that

the demand for energy and growth will not slow.

The Target: To consume all domestic

resources in the next ten years

Turkey’s primary energy demand is

predicted to increase by 90% and reach 218 billion TOE (tons of oil equivalent)

by 2023, up from around 115 million TOE in 2011. In 2011, plans had the share

of natural gas in primary energy being reduced from 32% to 23%; coal, at a 31%

share of primary energy, is set to increase to 37%. According to the Ministry,

in 2023 the percentage of nuclear energy will rise to a 4% share of primary

energy, up from zero. Interestingly, hydroelectric (currently 4%) and other

renewable energy resources (currently 6%) are not set to change at all, as is

the case with petrol (2011: 27%; 2023, projected: 26%.) Even if this

paper’s targets are met and all the hydroelectric potential is tapped, it will

not effect a proportional change because overall demand will have doubled.

Obviously, the ‘‘strategic plan’’ is not interested in any radical moves

towards sustainability in Turkey. By 2023, a full 90% of Turkey’s primary

energy demands will be generated by non-renewable resources: coal, oil, and

nuclear. This figure includes the Ministry of Energy’s planned use of half of

the nation’s wind energy potential (48,000 megawatts*6) and the energy generated

by the hydroelectric plants constructed on almost every river in Turkey. The

government’s own data suggests that Turkey’s economic growth cannot be

sustained by domestic resources alone; almost all the ‘‘domestic resources

approved by the government’’ will be consumed within ten years.

Leaving aside environmental problems

that will be caused by the combustion of coal, oil, and nuclear energy for the

moment, the strategic plan doesn’t even provide any notable progress in making

Turkey less dependent on foreign energy sources. Almost all of the nuclear

energy, oil, and natural gas that will form 53% of 2023’s primary energy

generation will have to be imported. It is also important to note that the

nuclear fuel providers and operators of the planned nuclear plants will be

foreign companies. In addition, not all of the coal used in coal’s 37% share of

total generation will be domestic. In 2011, 10% of electric energy generated by

coal-burning power plants was generated with imported coal. New, planned

coal-burning power plants will add to the power generated by existing power

plants to generate even more electricity from coal in 2023. Today, power plants

running on imported coal with a total capacity of 6,000 megawatts are in the

process of review and evaluation from the Energy Market Regulatory Board in

anticipation of receiving their licenses. Taking into account the imported coal

and natural gas power plants that have applied for licensing, we can calculate

that Turkey’s foreign energy dependency is currently around 70% and that it

will not change much by 2023, despite the fact that the entire potential of

domestic coal and hydroelectrics will be generating energy.

Leaving aside environmental problems

that will be caused by the combustion of coal, oil, and nuclear energy for the

moment, the strategic plan doesn’t even provide any notable progress in making

Turkey less dependent on foreign energy sources. Almost all of the nuclear

energy, oil, and natural gas that will form 53% of 2023’s primary energy

generation will have to be imported. It is also important to note that the

nuclear fuel providers and operators of the planned nuclear plants will be

foreign companies. In addition, not all of the coal used in coal’s 37% share of

total generation will be domestic. In 2011, 10% of electric energy generated by

coal-burning power plants was generated with imported coal. New, planned

coal-burning power plants will add to the power generated by existing power

plants to generate even more electricity from coal in 2023. Today, power plants

running on imported coal with a total capacity of 6,000 megawatts are in the

process of review and evaluation from the Energy Market Regulatory Board in

anticipation of receiving their licenses. Taking into account the imported coal

and natural gas power plants that have applied for licensing, we can calculate

that Turkey’s foreign energy dependency is currently around 70% and that it

will not change much by 2023, despite the fact that the entire potential of

domestic coal and hydroelectrics will be generating energy.

The constantly increasing energy

demand

We have briefly summarized the

energy aspect of the government’s strategic targets and have discovered that

the results of such a strategy would not create a solid energy future for

Turkey. There is a close relationship between energy and growth. In an economy,

the measure of growth is defined as the increase in the production of goods and

services. The production of more goods and the providing of more services go hand

in hand with increased energy consumption. It is important to remember that the

consumption of energy itself supports growth. But, at the same time, there are

consequences and damage caused by the energy that is considered the fuel for

growth. Mines and energy power plants cause irreversible damage to the

environment and increase Turkey’s contribution to global climate change. Since

1990, greenhouse gases emitted by Turkey have increased 124%; Turkey’s

emissions rate of 5.7 tons per capita is above global average.*7 Even ignoring

environmental issues, we are still faced with questions: Can Turkey’s energy

resources support Turkey’s anticipated growth? How much, and in what ways does

Turkey want to grow? The answer to this question is also the answer to

the first; how much Turkey wants to grow determines if Turkey’s energy

resources will be sufficient or not.

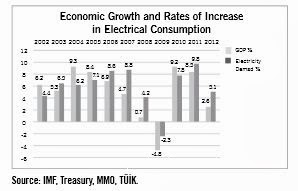

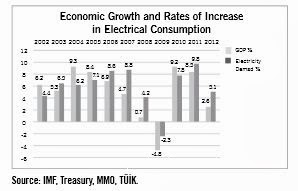

Turkey’s 8.8% economic growth in

2011 is used as an example to other nations struggling with economic crises,

but it is still a country where the quality and sustainability of growth is in

dispute. Here the word sustainability has two meanings. The first includes an

evaluation on an environmental basis, which is often neglected in Turkey. The

second describes the consciousness of growth. Let’s look at the second definition

of sustainability first. Turkey has been growing for 13 successive quarters.*8

Growth rates year-to-year have varied, but overall there is definite growth.

The global economic crisis did not cause a serious financial bottleneck in the economy

of Turkey, but it has caused zigzags on growth charts. After the economic

crisis of 2001, the economy of Turkey slowed to a growth rate of 5.7%, and only

crawled up to 6.2% in 2002. Record growth over this 12-year period was in 2004

with 9.4% growth. In 2008, after a dip, there was hardly any progress with a

recorded 0.06% growth, followed by recession at -4.8% in 2009. After that

year’s recession there were two years of booming growth, which again slowed in

2012 to 2.2% growth. Every 7 or 8 years, the economy of Turkey seems to suffer

a financial bottleneck due to internal and external factors. Although its

growth is often compared to China’s, growth in Turkey is not growing

exponentially like it is in China. Turkey’s growth is marked by fits and starts,

but shows an overall increasing trend.

At first glance, it seems that

demand for energy grows in parallel with an increase in growth. In 2000-2011,

economic growth increased 4.36% overall, and the demand for electrical power

increased 5.6%. In 2004, 2005, and 2010, we saw the opposite trend: As growth

registered, respectively, 9.3%, 8.4%, and 9.2%, the rise in the consumption of

electricity remained 6.2%, 7.1%, and 7.8%, respectively. In 2007, when growth

was 4.7%, demand for electric power increased by 8.8%. The following year,

Turkey’s economic growth was not substantial (0.7%) but the demand for electricity

rose by 4.2%. Instead of insisting on a correlation, it seems wiser to talk

about a “lack of control.” Not only does this observation reject the idea

that there is a general increase in the demand for electricity, but it also

highlights the fact that it is difficult to use and illusionary to expect

domestic growth rates to estimate energy or electricity demand. An examination

of electrical power demand shows us how these estimates are misleading.

In 2005, the Turkish Electricity

Transmission Company (Türkiye Elektrik İletim Anonim Şirketi, abbreviated as

TEİAŞ) estimated that energy demand in 2001 would be 262 billion kilowatts per

hour. However, in 2011, Turkey’s electrical demand remained steady at 230

billion kilowatts per hour. TEİAŞ’s 2005 estimate was off the mark by 12%. Some

might say that with such a vibrant electric market, it is difficult to predict

even six years into the future, and that 12% is an acceptable rate of error.

But there is another example: According to its high-demand scenario, TEİAŞ’s

October 2010 capacity report estimated that that year’s electrical demands

would stay just below 220 billion kilowatts per hour, a forecasted annual

increase of 5%. However, the actual annual increase was 9%. Obviously, the

issue is not only the accurate estimate of electrical demand for the future,

but for the present. If demand is not managed in Turkey, then we will be forced

to continue attempting to solve the energy problem based on policies of supply.

Without access to unlimited energy resources, this will inevitably cause

difficulties in the financial and political arenas.

The Ministry of Energy and Natural

Resources’ estimates point to a continuous increase in already high rates of

energy demands. Both TEİAŞ scenarios insist on continuing with the same

operational scheme despite the miscalculations from the previous years. In the

scenario where the demand for electricity is low, the annual average increase

is expected to be 6.5%; in the high-demand scenario, the average expected

increase rises to 7.5%. This means that in 2020, the gross demand will be

between 400 and 433 billion kilowatts per hour. Considering that consumption in

2012 was around 240 kilowatts per hour, those figures would indicate a

significant increase in demand over the next eight years. The Ministry may not

give such things as solar energy or energy performance much consideration, but

not everyone is of the same mind. Necdet Pamir, Chairman of the Energy

Commission of the opposition Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk

Partisi, or CHP) believes that Turkey has the potential to generate enough

power even for the high-demand scenario: "Last year Turkey consumed 241

billion kilowatts per hour of electricity. The fact is, our resources are at a

level capable of meeting an average of 7% growth. We have a potential 100

billion kilowatts per hour from hydroelectric power plants, 12 billion

kilowatts per hour from wind energy, 16 billion kilowatts per hour from

geothermal energy and 380 billion kilowatts per hour from solar power. There

are also 116 billion kilowatts per hour from lignite and 35 billion m³ from

biogas. So in total there are resources adding up to over 700 billion kilowatts

per hour. This is surely far over our consumption of 241 billion kilowatts per hour".*9

But the picture Pamir paints doesn’t

make environmentalists happy, either. For many environmentalists in Turkey, the

use of coal and hydroelectric power plants crosses a red line. The important

issue is how to solve the energy problem without depleting all potential energy

sources. This can only be achieved through questioning energy performance and

demand. The so-called necessity for growth that pushes Turkey to consume more

energy itself needs to be discussed. There should be specifications for which

energy-intensive industries should be active and which should not be allowed to

operate or be

capped.

The Ministry of Energy and Natural

Resources estimates point to an ever-increasing high demand for energy. This is

not a position that is particular to the government; often, it misguides those

–like investors– who don’t know Turkey in great detail. These estimates are the

expression of a desire; they do not actually reflect the indication that energy

demand will increase. Supporters of classical financial theories for Turkey’s

sustained growth are dreaming of great increases in the per capita GDP.

Executives in the energy sector who believe in the probability of increased

demand have prepared their own scenarios based on continuous demand. Perhaps

both sides have the wrong idea; neither has considered using energy more

efficiently and more sustainably through a low-rate increase or even decreasing

energy demand. Neither has considered an economy composed of using less energy

to attain the same per capita GDP goals instead of relying solely on the idea of

an economy composed of energy-intense sectors manufacturing products with

higher added value. Turkey’s demand estimates have not –at least no yet–

reflected this idea. Germany, for example, produced 100 units of per capita GDP

by consuming 100 units of energy in 1990; in 2010, it produced 131 units of per

capita GDP by consuming 94 units of energy. The efficient use of energy has a

great role in this achievement.*10

The Ministry of Energy and Natural

Resources estimates point to an ever-increasing high demand for energy. This is

not a position that is particular to the government; often, it misguides those

–like investors– who don’t know Turkey in great detail. These estimates are the

expression of a desire; they do not actually reflect the indication that energy

demand will increase. Supporters of classical financial theories for Turkey’s

sustained growth are dreaming of great increases in the per capita GDP.

Executives in the energy sector who believe in the probability of increased

demand have prepared their own scenarios based on continuous demand. Perhaps

both sides have the wrong idea; neither has considered using energy more

efficiently and more sustainably through a low-rate increase or even decreasing

energy demand. Neither has considered an economy composed of using less energy

to attain the same per capita GDP goals instead of relying solely on the idea of

an economy composed of energy-intense sectors manufacturing products with

higher added value. Turkey’s demand estimates have not –at least no yet–

reflected this idea. Germany, for example, produced 100 units of per capita GDP

by consuming 100 units of energy in 1990; in 2010, it produced 131 units of per

capita GDP by consuming 94 units of energy. The efficient use of energy has a

great role in this achievement.*10

Turkey has a lot of work to do in

energy efficiency. In order to achieve an increase of €1000 per capita GDP,

Turkey must consume an equivalent of 233 kilograms of petrol. The same economic

growth is achieved with the equivalent of 147 kilograms in Greece, 80 in

Switzerland, 141 in Germany, 123 in Italy, and 92 in Ireland.*11 Put in

different terms, Turkey consumes 2 to 3 times more energy than many countries

in Europe to produce the same product or to provide the same service. Even more

disheartening, while the rest of the world is trying to find new ways to use

energy more efficiently, Turkey has shown no development in this regard since

1990. In that year, Turkey consumed 242 kilograms of petrol to add €1000 to the

per capita GDP. In European countries whose economies are similar to Turkey’s,

there has been a marked change towards using energy in a more intelligent

manner; Turkey has not followed suit.

Turkey has a lot of work to do in

energy efficiency. In order to achieve an increase of €1000 per capita GDP,

Turkey must consume an equivalent of 233 kilograms of petrol. The same economic

growth is achieved with the equivalent of 147 kilograms in Greece, 80 in

Switzerland, 141 in Germany, 123 in Italy, and 92 in Ireland.*11 Put in

different terms, Turkey consumes 2 to 3 times more energy than many countries

in Europe to produce the same product or to provide the same service. Even more

disheartening, while the rest of the world is trying to find new ways to use

energy more efficiently, Turkey has shown no development in this regard since

1990. In that year, Turkey consumed 242 kilograms of petrol to add €1000 to the

per capita GDP. In European countries whose economies are similar to Turkey’s,

there has been a marked change towards using energy in a more intelligent

manner; Turkey has not followed suit.

The secret to producing more with

less energy lies in the choices made in transportation, production, housing,

and industry. When more efficient machinery is used, when buildings are

insulated and public transportation is developed, the demand for energy

decreases, thus allowing for demand management. If we can manage the demand and

use of energy in an efficient way, there may be no need to construct the many

power plants that are currently underway, and economic growth could be realized

while consuming less energy.

Consumption as the source of growth in Turkey

We know that domestic demand

contributes greatly to growth in Turkey, so it is not surprising that the

present government would be encouraging a population boom.*12 If individual

consumption decreases, growth comes to a halt. An increase in population contributes

to growth through the corresponding increase in demand for consumer goods and

services. Despite its current population of 75 million, the government of the

Republic of Turkey is preparing a stimulus package for families with multiple

children. There is more reason for the government to act now because of the

anticipated decrease in population after 2050.

According to 2013 statistics, the

average number of children per woman in Turkey is two. If the downward trend

continues, Turkey’s population is expected to reach 84.24 million in 2023. The

population will peak at 93 million in 2050 before it begins to dip. In 2023,

the elderly (65 years and older) population is expected to reach 8.3 million,

or 10% of the total population. In 2075, the elderly population will constitute

an estimated 27% of the total.*13 Perhaps Prime Minister Erdoğan’s assertion

that families should have at least three children has as its foundation in the

fact that the elderly population will not be able to sustain domestic demand. Erdoğan

should not be concerned about the 2075 proportion of the elderly to the total

population, whose percentages are comparable to current rates in Europe. On the

contrary, he should be worried that the Turkish economy - without any

structural change - will be dependent on domestic demand for growth even 60

years from today. In many European countries - Sweden, Portugal, the United

Kingdom, Austria, and Finland, for example - the elderly already constitutes

27% of the total population.*14 Turkey’s booming construction industry, and its

activated commerce and transport sectors might well be the reasons behind the

government’s support of families with many children, but ecologically it is not

sustainable as a comparison between Turkey’s biological capacity and its

ecological footprint will tell us. In Turkey, the ecological footprint of per

person consumption is 2.7 global hectares; that is over 50% of the global

biological capacity. In other words, if everyone in the world consumed as much

as a citizen of Turkey, we would need 1.5 planets. The most striking data from

“Turkey’s Ecological Footprint,” a report compiled by the WWF and the Global

Footprint Network, is as follows: Despite the stability of the

Ecological Footprint per capita in Turkey, the footprint of consumption has

increased 150% in total. The main reason for this increase is the great

population increase that occurred from 1961 to 2007.*15

Considering that the individual

consumption rate hasn’t changed over the long term and that consumption increased

with the population increase (although those born in the 2000s tend to consume

more than those born in the 1960s) it is understandable why families in Turkey

–a country where consumption means growth– need to have more children to

sustain it. But understanding alone will surely not help Turkey reduce

ecological damage.

Other data presented in the report

is even more important. In the 1990s, Turkey was able to keep its ecological

footprint and its biological capacity in line, but since 2002 its ecological

footprint has been growing rapidly and since 2006 its biological capacity has

been decreasing.*16 We must evaluate the realization of the AKP’s growth

policies since their rise to power in 2002 with the subsequent increase in

Turkey’s ecological footprint as well as the decrease in its biological

capacity; Turkey’s growth policies aren’t only increasing energy consumption;

they are laying the foundations for ecological problems.

The very idea that this growth

policy and the excessive energy consumption that goes with it can be supported

by domestic resources alone must be called into question. Although it is

possible to have a balanced economy with only imported energy, like South

Korea, it wouldn’t be possible without exporting a large quantity of higher

added value products. There is another way for Turkey and for other countries.

Rather than trying to meet limitless consumption with limited resources, Turkey

could limit its consumption and allow the manufacture of primary products or

put caps on the arms industry.

One might find this too radical as a

suggestion. However, global temperatures could go up 1.5-2.5 degrees Celsius,

causing the extinction of various species of plants and animals. Now let’s ask

ourselves again: Is it really radical to suggest that we control the use of

resources expended on the production of luxury automobiles and combat

aircrafts?

Footnotes

*1.

In the 2010-2014 Strategic Plan of the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources

of the Republic of Turkey this rate is announced as 73%, p: 22.

*2.

Turkey’s Natural Gas Market: Expectations and Developments 2012, Deloitte, p:

18.

*3.

Strategic Plan of the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources of the Republic

of Turkey, 2010-2014: p: 24.

*4.

Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources of the Republic of Turkey Annual

Budget Presentation for 2013, p: 70.

*5.

Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources of the Republic of Turkey, An Outlook

on Energy in Turkey and in the World Presentation, transparency 19.

*6.

This data was last viewed on May 12, 2013 at

http://www.enerji.gov.tr/index.php?dil=tr&sf=webpages&b=ruzgar&bn=231&hn=&nm=384

&id=40696. 48,000 mw indicates the installed capacity of units constructed

in regions with winds of over 7 m/s.

*7.

TÜİK, Inventory of the Emission of Greenhouse Gases, 1990-2011.

*8.

This data was last viewed on May 12, 2013 at

http://www.bloomberght.com/haberler/haber/1329715-turkiye-2012de--2-2-buyudu.

*9.

“We have the energy potential to meet seven per cent growth,” Dünya Newspaper.

This data was last viewed on May 12, 2013 at

http://www.dunya.com/yuzde-7-buyumeyi-karsilayacak-enerji-potansiyeline-sahibiz-187752h-p2.htm

.

*10.

Climate Protection and Growth, Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature

Conservation and Nuclear Safety, p: 13.

*11.

Eurostat data for 2010, May 21, 2013.

*12.

Growth and Structural Problems in the Economy of Turkey, BETAM Research Notes,

edited by Prof. Dr. Seyfettin Gürsel.

*13.

TÜİK, Population Projections 2013-2075, February 14, 2013.

*14.

Eurostat, Projected Old-Age Dependency Ratio.

*15.

Turkey’s Ecological Footprint, WWF Turkey and the Global Footprint Network, p:

7.

*16. Turkey’s Ecological

Footprint, WWF Turkey and the Global Footprint Network, diagram 9.